The letter below was written in 1968 by a former Feldwebel of the Fahnenjunkerschule Posen. It’s writing style is unusual and I tried to keep it that way when translating it. Short sentences, dry writing style and written in the present tense it contains some sentences that are quite hair-raising.

Photos have been taken from the files attached to the collection of letters. Maps have been produced by the Association of Poznan Fighters to accompany this letter.

On the 18th of January 1945 I was a trainee in training course 18a of the Infantry officers school Poznan (Kurs 18a, Schule V für Fahnenjunker der Infanterie Posen). I had joined the army in autumn 1942 and had been promoted to Unteroffizier, serving in Grenadier-Regiment 401, in June r 1944.

It is on the 18th in the Barracks of Kuhndorf when there is a call for volunteers to form a so-called “counterstrike-reserve” (Gegenstoßreserve).

As I only hear “Reserve” I ignore it and do not react. Many of my comrades volunteer as they think the emphasis lies on the word “Counterstrike”. Now I volunteer aswell. We expect to be deployed in the East soon.

In the Hardenberg school the Battlegroup gets formed. I get transferred to Gegenstoßkompanie Lt. Werner (missing). Later the company was taken over by Leutnant Schierts (missing).

The men we are supposed to lead make a good impression and are all around 30 years of age. Not one youngster among them. Stray soldiers, separated from their units, most with a good amount of combat experience. Arms and equipment get distributed and we march of to Fort Brüneck (Map No. 7). There was a factory inside Fort Brüneck. There was a large machine hall and another large hall for draftsmen which had one wall made of glass. It was there when we heard that Fort Witzleben had fallen.

Our first order is armed reconaissance against Lawica, a village near the airport, into which the enemy had penetrated (Number 2 on the map).

Trucks bring us to the airport where a Leutnant of the Luftwaffe with 20 men is waiting to reinforce our platoon. When we arrive we get told that the Luftwaffe Leutnant is take over command during the operation. Handgrenades get distributed and with surprise we hear that our Luftwaffe comrades do not know how to use them. We need to give them some basic instructions.

Our artillery is firing eight rounds in support. Two shells hit the pile of gravel we are covering behind and explode right in front of our noses. Some Luftwaffe soldiers get sick, a couple start to vomit. Concrete tubes and more piles of gravel line the road and using them as cover we manage to advance quickly and soon come up to an observation tower. Behind it is open field but I spot a foxhole in the ground about 70 meters away. Under the cover of a machine-gun i sprint towards it in the hope of spotting another place where to take cover. Suddenly a soviet machine gun is opening up on me. My machine-gunner comes running up to me and an intense firefight developes with the enemy who is covering in some houses and gardens about 100 meters away. Feldwebel Kemper comes up behind us, it is getting crowded in our foxhole. We come to the conclusion that there is no more cover ahead of us. Kemper sprints back to redirect our attack. The soviets now use an anti-tank gun and mortar shells begin to detonate around us. We have to get back and are lucky to reach the observation tower without getting hit. One man (forgot his name) gets severely wounded by a rifle round to the abdomen. Soviet reinforcements are arriving the Luftwaffe Leutnant gives the order to retreat. We know enough and return to Brüneck.

When we return we find some StuG assault guns waiting in front of the fort and get told that there will be a larger attack soon.

ATTACK ON LENZINGEN (Number 3 on the map)

We organise material to camouflage the helmets and uniforms of the men not wearing camo suits and uniforms. When the attack starts we make good progress. On our left there is a Waffen-SS unit. Assault guns are moving forward in support. Crossing a gloomy brickyard we reach the outskirts of the village. We pass a row of about 30 dead comrades. All show signs of mutilation. Most have their ring fingers cut off. They must have been killed when the village was first attacked by the enemy. A SANKA (ambulance vehicle) is standing close by, it is riddled with bullet holes. The road is covered with bandages and medical instruments.

Suddenly we receive fire from Fabianowo, a village on our right flank. Unteroffizier Ewald Schmidt and his men are sent there while we continue to advance into the village. Soon one of Schmidts men come running up behind us. Schmidt has been ambushed.

I at once report to the company commander requesting to be allowed to rescue Schmidt. Me and Schmidt have known each other for two years.

We reach the village and start searching the buildings on both sides of the road when we get attacked by russian ground attack aircraft. We have to retreat. I have never seen Schmidt again. We repel a counterattack. Feldwebel Tattenberger, another old comrade of mine destroys two T34s with Panzerfausts. We have to clear Lenzingen on the evening of the 24th of January and move into position south of Fort Brüneck (Number 4 on the map).

Tattenberger

We can observe endless columns of soviet trucks, infantry, tanks and guns driving from Lenzingen to Dembsen without any encountering any resistance. We know that sooner or later this mass of material will be moving against us. Our artillery stays silent! Flak and Pak would have had countless targets but nothing happens! We have strict orders to conserve ammunition. In Lenzingen I got hold of a russian Schpagin Mpi with which I fire into their ranks. Even if the distance is not ideal some russians dive into cover. An excellent weapon!

With a reinforced group I secure the open pasture between Fort Brüneck and Dembsen against tanks. We secure the gardens and an old, free-standing house. In the night a dual 20mm flak gun (self-propelled) arrives to support us. That day Leutnant Werner fails to return from a combat patrol (missing since then).

On the evening of the following day we get attacked by five tanks coming at us in line abreast. We are ready for them. About 60 meters in front of us they turn right towards the road from Dembsen to Gurtschin which is barely visible under the snow. The ground there is undefended, the only thing visible there are four lonely abandoned artillery pieces of a german battery.

The road is passing the driveway toward to the Fort! I know that the Flak is positioned somewhere close but will the comrades notice the danger approaching them before it is to late? Passing command to one of my men, I and another comrade sprint across the open ground towards a board fence enclosing a property adjacent to the road. We carry five Panzerfausts with us and I hope to able to hit the tanks from there. As soon as the tanks reach the firm ground of the road they increase their speed and before we manage to reach the fence we hear the sound of tank guns followed by a mighty explosion. We are too late and find the burning remains of the Flak and the torn bodies of our comrades.

One of our AT guns manages to destroy two of the T34s. One of them spews a huge jet of flame, its turret rises into the air and hits the ground about 10 meters away. The remaining three turn around and try to escape. I start chasing them but get recalled by Hauptmann Lohse who tells me that we are ordered to regroup all available personnel for a counter attack. We move into our positions close to a railway embankment (Number 5 on the map). Close to the railway crossing lie dozens of bicycles, I remember thinking about how they might have got there.

We receive heavy artillery fire from the direction of Dembsen and take cover below some railway wagons. The gravel on the ground makes every detonation even more lethal. The ground shakes, a comrade in front of me starts screaming like a stuck pig. He is not wounded, he is afraid.

The night of the 27th is freezing cold. Frank, the comrade who carried the Panzerfausts for me asks if he can act as machine gunner in my group. normally he serves in 4. Gruppe (4th group) and is only with us as a reinforcement. Later he will prove himself to be an excellent gunner and soldier.

Tannenbergstrasse

We still have not received an order to attack. A company turns up and I notice that I know some of the faces. Its our company. He report to the commander, who speaks with Hauptmann Lohse who allows us to leave. We move into the Tannenbergstrasse (Number 6 on the map) and take quarters in some of the houses. I remember looking out of a window seeing fires blazing all around me.

On the 28th of January we march towards Hill 104 “Berlin heights” (number 7 on the map). Soon we are targeted by indirect machine-gun fire. Halfway up the slope there is a well-built position, in front an anti-tank ditch. The only defending unit is a 8.8cm Flak gun.

We pass our own defences and develop into formation to attack a large block of houses lining the road. Suddenly when we close with the buildings, a huge mass of russian infantry oozes out between them. At least one full batallion is charging towards us. Fighting this mass on open field and in close combat would be suicidal. We retreat to our position on the hill. When the russians get closer we open fire. The soldiers manning the Flak gun are opening fire aswell and I notice that most of them are boys not older than 16 or 17 years.

The Russians suffer heavy losses, start to retreat but get forced back by officers with raised pistols. Finally even this starts loosing effect and they retreat behind the buildings to regroup before carrying forward another attack. This time the Flak shreds the attackers before they even have a chance to develop. Again the enemy takes heavy losses. I notice that the boys manning the Flak are wearing their white nightshirts over their uniforms making for an effective snow camouflage.

We are able to hold and the russians start using mortars. In the late evening I notice two enemy tanks on our right flank. Leutnant Schiers, Passerath, Heinrich and myself are fetching some Panzerfausts and make our way towards them.

Our camo uniforms do not help us and as soon as we leave our position we are targeted by mortar fire. We manage to reach a depression in the ground and hope to be able to open fire from it, sadly our Panzerfausts are still out of range.

The next day (29th of January) our position is targeted by mortar fire and enemy snipers. I try to locate the enemy snipers with my binoculars when a mortar shell exploded only a couple of meters to my left. I get wounded by a bit of shrapnel in the upper arm.

The Flak receives a direct hit. Its carnage. Most of the boys are dead, one stumbles in my direction. His white nightshirt is had is stained with red and black. His ears bleed and he is crying.

We retreat. We have to. In bright daylight under constant mortar and sniper fire!

Reaching the Tannenbergstrasse I make my way to the First Aid Station inside Fort Grolman. (Number 8 on the map).

The catacombs below it are crowded with the wounded. The air is terrible and I remember the overpowering stench of Valerian. A medic tries to remove the shrapnel in my arm by using a pair of forceps. He fails. I get a tetanus injection, a dressing and a cup of Valerian Tea. I prepare to leave when the medic asks if he can accompany me. The fresh air above is a treat. The medic looks tired and I remember he had very light blue eyes. He smiles and wishes me luck when I leave.

Back at Tannenbergstrasse I have to take over the Platoon. Kemper had been wounded.

On the following day (30th of January) we are still in Tannenbergstrasse. Inside the city we hear the howl of Stalin’s-Organs.

We are ordered to Fort Grolman. There we get to eat hot pea soup, which tastes wonderful. At the evening we get guided into positions in front of the Forst (facing east – number 10 on the map). In line we move along a slightly curved road. Left of us is open field, some gardens can be seen 200 or 300 meters away. On our right there is there is a ditch, a fenced garden with two houses. We come up to a crossing where there is a dug-in 8.8-Flak.

When come closer the, Flak gets fired upon with mortars and receives a direct hit. The crew seems to be ok and tries to find cover in the ditch. An enemy machine-gun now opens up on us with explosive ammunition and the mortars start to switch their fire on us. Enemy riflemen open fire from the gardens. One comrade is hit by explosive rounds. The wounds look terrible. Mortar shells hit the roof of the house on my right. Feathers rain down on us. Someone must have stored bedding there.

I receive the order to occupy the houses and the garden. I yell to the company commander that we will try to crawl up to the fence below the machine-gun fire. He shakes his head, but allows me to try taking only 1st Group with me. It works and we manage to get into the left house without taken any losses. We enter the basement and set up an MG42 in one of the windows. Our gunner manages to silence the enemy fire.

The Russians bring in a “Ratsch-Bumm”* and at once score two direct hits. The shells hitting the walls on the left and right side of our window. The wooden crates on which we set up our machine gun collapse, our eyes and mouths are full of dust and grout. Our ears are ringing. Its hot and impossible to breathe. Before I can order it Frank grabs the MG42 and runs up the stairs setting the gun up in a window of the first floor. The russian gun has ceased firing its crew is not visible, the russians must think they got us. When comrades in the basement open fire with rifles and machine pistols the soviet gun crew comes running up from behind a concrete pillar standing next to the entrance of garden. This was the moment Frank had been waiting for. His salvo is precisely on target. The Russians don’t even manage to reach their gun.

A runner informs me that Passerath, Heinrich and another large part of the Platoon have been wounded. Kronberg and Schaffrath are now Groupleaders. On the evening of the 30 of January we get relieved by another platoon commanded by Leutnant Phillip.

Inside the Fort (Number 11 on the map) we get briefed by Major Reichardt who tells us that we lost radio contact to the citadel. As the sounds of combat coming from the direction have ceased aswell we expect that the citadel has fallen. He talks about an expected german counter attack coming from the north-west. We will break out into this direction to link up with the attacking german troops, there we are supposed rearm and resupply and then to follow the attack to liberate Poznan. As we are lacking the heavy weapons and ammunition to repel the expected Russian attack, the plan sounds reasonable. Reichardt had been our teacher at officers school and we trust him. The breakout is scheduled for the same night (30th to 31st of January 1945). Our Battlegroup is down to about a third of its original strength. We number no more than 100 men.

Soldiers of the Strotha bastion reinforce us. They bring their wounded with them which they transport on sleds. Reichardt orders the wounded to be brought to Fort Grolman where by now huge flags bearing the Red Cross have been installed. The Major expects us to reach the first german troops within two days and we equip ourselves with food accordingly. Soldiers of the Strotha bastion reinforce us. They bring their wounded with them which they transport on sleds. Reichardt orders the wounded to be brought to Fort Grolman where by now huge flags bearing the Red Cross have been installed. The Major expects us to reach the first german troops within two days and we equip ourselves with food accordingly.

When we reach the soviet lines we cross a line of enemy tanks. The Russians point their searchlights into our direction and he have to lie flat in the snow to avoid detection. We wait for the tanks to open fire. Will our Panzerfausts be sufficient to survive whats coming? Not a sound can be heard, the Russians do not shoot. Slowly we crawl into safety.

The next day we hide in bales of straw. A “sewing machine”* circles above our position, it must have followed our tracks in the snow. After a while it disappears. We leave our hiding places and hurry on through deep snow.

Later on we hide in a polish farmhouse near Szczepy. We throw straw on the ground and fall into sleep within seconds.

“DER IVAN!” – The shout tears us out of our sleep. One of the polish farmers must have alerted the Russians.

Enemy fire rips through the walls of the barn. Using some handgrenades we manage to get us enough time to pull on our soaked boots and to gather our equipment. The door desintigrates under the salvo of a machine pistol. A comrade standing next to me collapses when the shots rip into his body. He is still alive and begs us to take him with us. I take his MP-44 assault rifle. It is hard to leave the comrade behind.

Firefights with attacking Russians in which I use my new assault-rifle. A great weapon. Exiting through the windows we manage to reach a nearby forest.

We cross the frozen Warta near a village (Wronki). When searching the houses we run into a Russian officer who draws his pistol and kills Hauptmann Ulrich. We launch an attack on the office of a forest warden which is used by the Russians as a supply point. Close combat with Russian soldiers. I will spare you the details. Many Russians are drunk. They must have behaved like animals. We find a barn filled with dead women and children. Our patrols inform us that all possible crossing points are well guarded by the enemy. Major Reichert makes the decision to dissolve the Battlegroup and orders us to try to reach the german lines in small groups. The sound of fighting carries over from the south-west, the Russians are assaulting Landsberg.

We cross the frozen Warta near a village (Wronki). When searching the houses we run into a Russian officer who draws his pistol and kills Hauptmann Ulrich. We launch an attack on the office of a forest warden which is used by the Russians as a supply point. Close combat with Russian soldiers. I will spare you the details. Many Russians are drunk. They must have behaved like animals. We find a barn filled with dead women and children. Our patrols inform us that all possible crossing points are well guarded by the enemy. Major Reichert makes the decision to dissolve the Battlegroup and orders us to try to reach the german lines in small groups. The sound of fighting carries over from the south-west, the Russians are assaulting Landsberg.

I move out with a group of three comrades. Near Gottschimm we spend the day resting in an abandoned house, resting and cleaning our weapons Suddenly the door opens and two Russians or Poles wearing heavy fur coats enter the house. Frank threatens them with a half of his P08 until we manage to assemble our guns. We didn’t place a guard as we had watched the house and the surrounding area for quite a while. A mistake. We allow our visitors to leave without doing them any harm, but hurry off soon after they have left. We are lucky and find a fisherman who takes us across the Netze in a small boat. On the other side we meet two comrades who join up with us. Near Zanzthal we have to wait many hours close to a busy road. We watch the endless russian columns until a large enough space makes it possible to cross undetected.

We are lucky and find a fisherman who takes us across the Netze in a small boat. On the other side we meet two comrades who join up with us. Near Zanzthal we have to wait many hours close to a busy road. We watch the endless russian columns until a large enough space makes it possible to cross undetected.

In a Mill near Tankow we meet a group of women and children hiding from the Russians. We hear the tales of Russian cruelties. One of the women, a young teacher, has her body covered with bruises and bite marks. She has been repeatedly raped. The women have flasks of Potato-Schnapps which they distribute among us.

In Farmhouse some kind people attend to my wound which is festering badly. They tell us that two Waffen-SS soldiers are hiding in a barn nearby, one of them with a severe shot wound. We visit the two comrades who at once want to join us. Taking turns two of us support and carry the wounded comrade and we manage to make good progress, but some hours later the wounded comrade is in so much pain that we have to carry him back.

This cost valuable time which we need to make good. To be faster we march along a road leading through a beech forest. Suddenly a shot rings out. There is a group soldiers on horseback behind us. The snow must have muffled the sound of the hooves. Using my assault-rifle I manage to empty a couple of saddles. We retreat, continuing to shoot, into dense forest. There we notice that the two comrades we had picked up after crossing the Netze have fled on their own.

Another rest in a farm. The inhabitants beg us not to open fire whatever will happen. The Russians would kill them and torch their farm.

We are resting in a hayloft above the stables. There is only a small amount of hay left as the Russians have carried most away. A couple of hours later a group of about 30 loudly shouting Russians comes riding into the farmyard. They must be the ones we fought earlier on. They round-up all the women and start raping a girl of about 12 years. We can’t do anything to help. It is terrible.

Later on they leave, taking the women with them. The remaining farmers tell us that the women are taken to do various labour for the Russians and would be returned in the night.

Schaffrath and myself are now covering Frank who is going to search another house close a crossroads for food. While we are watching a car with some Russians pulls up next to the house. Frank, who comes charging out of the house, grabs the coat of the Russian closest to him, presses his pistol into his body and pulls the trigger. The Russian screams and falls down. We open fire aswell. Frank is in close combat with 4 or 5 Russians and takes down another one. The remaining Russians jump into the car and speed away.

When we finally reach the Plöne Lake we try to cross it by boat, but have to return as its partially frozen. In a Fishermans hut we find some pig lard a bag filled with sugar. Provisions urgently needed.

We reach the canal linking the Lake Plöne with Lake Madü. A Russian patrol crosses nearby forcing us to hide in the water until it has passed. By dawn we have reached another barn; we rest and take turns acting as guards. Later we get woken by Schaffrath, there are Russians digging trenches nearby. Our situation is getting critical. German artillery is starting to fire, Russian patrols walk past our barn!

There is a village nearby, north of the canal. There is a little bridge, but our hopes are shattered when we spot Russian pioneers mining it. North of the canal the ground is swampy and it is there that we are going to cross now. During the night we place some wooden planks across the canal and manage to crawl across.

We continue crawling through swamp and come across a Russian machine-gun position. It is facing west and fires towards a railway embankment . We crawl towards it and are shocked when suddenly signal flares rise into the sky and Russian machine guns open up on us firing from the railway embankment. That does not make sense. Each movement is answered by a long stream of machine gun fire. We retreat and spend the night in a stack of hay close by.

North of us there is a Russian artillery position and some AT-guns. They are facing west aswell, towards the railway embankment! One AT-gun fires upon a chimney between the canal and the railway line. They score a direct hit and send bricks flying. The german lines must run along the railway embankment, we are sure of it. We have no idea how to place the Russian machine-guns that fired on us during the night.

In the following night we try it again. Using a furrow in the ground we rob towards the embankment. Each of us carries a handgrenade in case we encounter opposition. Coming closer we stop and listen into the night hoping to hear voices. It is when we see the familiar shape of a german Stahlhelm that we rise and run towards it – nearly getting shot by the Waffen-SS soldier wearing it.

We reached the german lines. Faces of grinning Waffen-SS soldiers all around us. We get cigarettes and Schnapps…we made it.

* RATSCH-BUMM = “Whizz-Bang” , German slang for Russian 76mm SiS-3 field gun

* SEWING-MACHINE / NÄHMASCHINE = Polikarpow Po-2

On 15 June 1889, Adelbert Theodor Edward (“Theo”) Wangemann started out aboard the four-master “La Bourgogne” on a trip to Europe on behalf of Thomas Alva Edison that was supposed to last for only a few weeks, but from which he was not in fact to return until 27 February 1890. Wangemann’s assignment during the first two weeks after arrival was to maintain the phonographs on display at the world’s fair in Paris, readjust them, furnish them with improved components, and train the personnel who operated them

On 15 June 1889, Adelbert Theodor Edward (“Theo”) Wangemann started out aboard the four-master “La Bourgogne” on a trip to Europe on behalf of Thomas Alva Edison that was supposed to last for only a few weeks, but from which he was not in fact to return until 27 February 1890. Wangemann’s assignment during the first two weeks after arrival was to maintain the phonographs on display at the world’s fair in Paris, readjust them, furnish them with improved components, and train the personnel who operated them

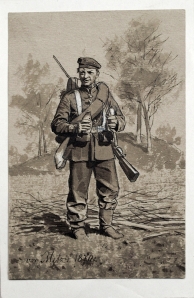

This impressive old gentleman is General Hellmuth von Gordon, General of the Prussian and later Imperial German Army and it is because of his family name I chose him to feature in this post. Hellmuth von Gordon was a direct descendant of the Scot John Gordon (the Gordons of Coldwells) who went to Poland as a merchant in 1716 as proved in a birth brieve dated to the 27th of June 1718 (a copy of which is found in the Aberdeen City Archives). One of his sons Joseph Gordon (later von Gordon), served as an officer in the army of Frederick the Great, rising to the rank of Oberstleutnant before getting raised into the Prussian nobility in Stargard in Oktober 1760.

This impressive old gentleman is General Hellmuth von Gordon, General of the Prussian and later Imperial German Army and it is because of his family name I chose him to feature in this post. Hellmuth von Gordon was a direct descendant of the Scot John Gordon (the Gordons of Coldwells) who went to Poland as a merchant in 1716 as proved in a birth brieve dated to the 27th of June 1718 (a copy of which is found in the Aberdeen City Archives). One of his sons Joseph Gordon (later von Gordon), served as an officer in the army of Frederick the Great, rising to the rank of Oberstleutnant before getting raised into the Prussian nobility in Stargard in Oktober 1760.