In 1980, a German military historian conducted a series of interviews which were used in a documentary on the Battle of Verdun. The documentary itself is largely forgotten. There never was a VHS version and it has not been shown on TV for at least 20 years. I have been searching for ages to get a copy of it. Yesterday a friend of mine told me he had found a copy which he had recorded on VHS.

In 1980, a German military historian conducted a series of interviews which were used in a documentary on the Battle of Verdun. The documentary itself is largely forgotten. There never was a VHS version and it has not been shown on TV for at least 20 years. I have been searching for ages to get a copy of it. Yesterday a friend of mine told me he had found a copy which he had recorded on VHS.

Due to this I am now able to present these interviews (without the framework documentary they were embedded in) on my blog. As subtitling and translating is very time consuming I only did four interviews right now. Will add more at a later date.

Today all of these men and all other German veterans of World War 1 have joined the ranks of the Great Army. Material like this that should be preserved and shared. I hope you will enjoy these clips as much as I do. Feedback is welcome.

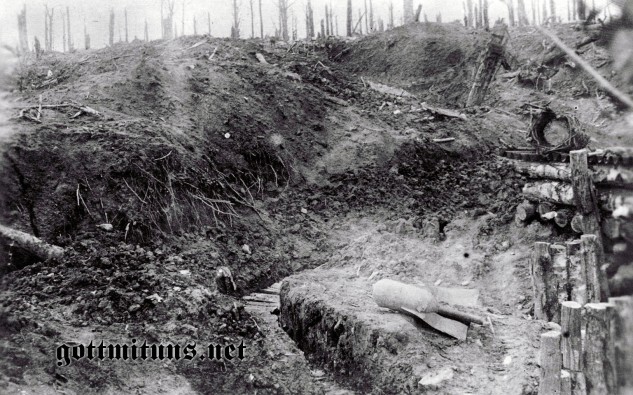

…. They had conquered a notorious hill. They had lived in trenches that had been alternately French and German. These trenches sometimes lay filled with bodies in different stages of decomposition. They were once men in the prime of their lives, but had fallen for the possession of this hill. This hill, that was partly built on dead bodies already. A battle after which they lay rotting, fraternally united in death….

(Georges Blond – Verdun).

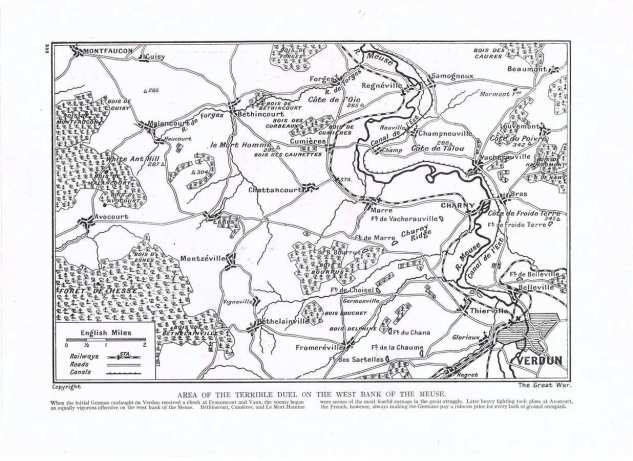

The Battle of Verdun is considered the greatest and lengthiest in world history. Never before or since has there been such a lengthy battle, involving so many men, situated on such a tiny piece of land. The main battle, which lasted from 21 February 1916 until 19 December 1916 caused over an estimated 700,000 casualties (dead, wounded and missing) on a battlefield was not even a square ten kilometres. From a strategic point of view there can be no justification for these atrocious losses. The battle degenerated into a matter of prestige of two nations…

“Before Verdun, Friday evening, February 18, 1916

I say good-bye to you, my dear Parents and Brothers and Sisters. Thanks, most tender thanks for all that you have done for me. If I fall, I earnestly beg of you to bear it with fortitude. Reflect that I should probably never have achieved complete happiness and contentment….Farewell. You have known and are acquainted with all the others who have been dear to me and you will say good-bye to them for me. And so, in imagination, I extinguish the lamp of my existence on the eve of this terrible battle. I cut myself out of the circle of which I have formed a beloved part. The gap which I leave must be closed; the human chain must be unbroken. I, who once formed a small link in it, bless it for all eternity.

And till your last days, remember me, I beg you, with tender love. Honour my memory without gilding it, and cherish me in your loving, faithful hearts.” – Letters of German Students, London, Methuen, 1929

The “Musketier” you see in the first clip is Herr Peter Geyr. He was a native of the Eifel (Rhineland-Palatinate) and so he speaks the beautiful dialect my grandmother spoke. He was born in 1896, served in Infanterie-Regiment “Graf Werder” (4. Rheinisches) Nr. 30 and joined the German army as a volunteer in 1915. He passed away in 1984.

The following film shows Unteroffizier Ernst Weckerling. He is probably the most well known German World War 1 veteran as he made an appearance in the PBS documentary “People’s Century”. Weckerling volunteered on August 14, 1914 and was part of the German forces that, at terrible cost, sought to “bleed the French army white” at Verdun. In 1916 he was holding the rank of Unteroffizier in Füsilier-Regiment von Gersdorff (Kurhessisches) Nr.80. His story of the “Potatoe Helmet Spikes” is just brilliant. You will not find thing like that in the history books.

The following film shows Unteroffizier Ernst Weckerling. He is probably the most well known German World War 1 veteran as he made an appearance in the PBS documentary “People’s Century”. Weckerling volunteered on August 14, 1914 and was part of the German forces that, at terrible cost, sought to “bleed the French army white” at Verdun. In 1916 he was holding the rank of Unteroffizier in Füsilier-Regiment von Gersdorff (Kurhessisches) Nr.80. His story of the “Potatoe Helmet Spikes” is just brilliant. You will not find thing like that in the history books.

The next one was hard to transcribe. Herr Ernst Brecher was a Musketier in 3. Thüringisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.71 which fought at Verdun as part of 38th Division from May to October 1916 before being moved to the Somme.

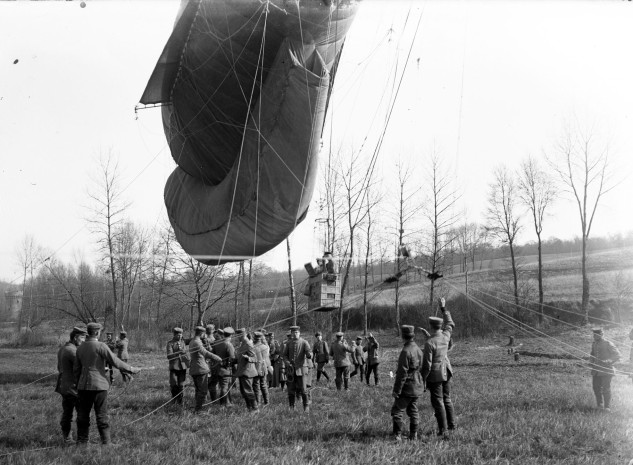

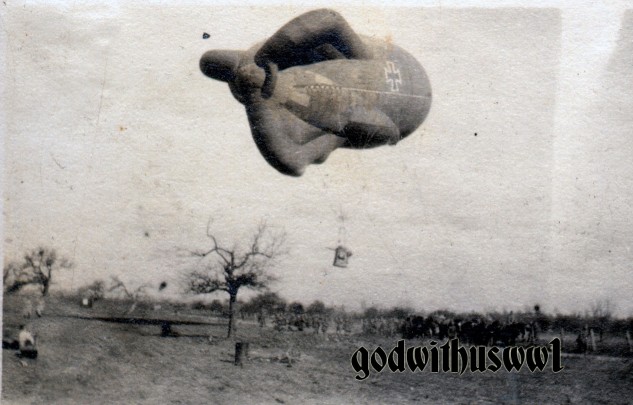

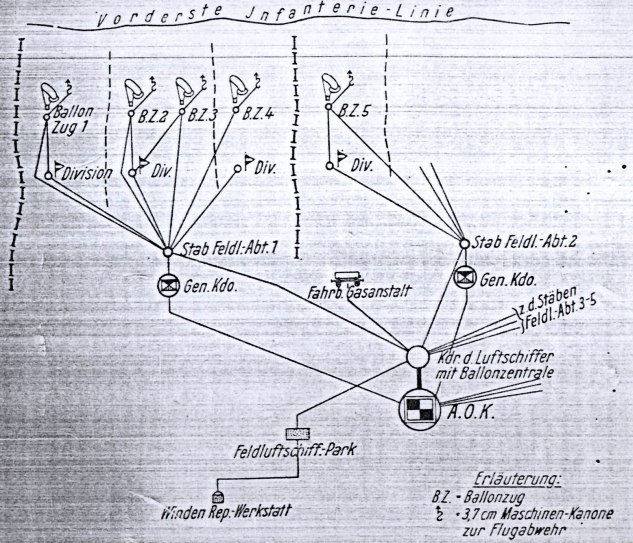

Herr Heinz Risse served as artillery observer in a Regiment of Field Artillery and tells us of his experiences in the fighting around the village of Fleury. He died on the 17th of July 1989 in Koblenz.

Johannes Kanth was born in 1896 and served as a Gefreiter in 1. Lothringisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.130.

Musketier Heinrich Dorn, served in a German Infantry Regiment and was drafted in 1916.

Egloff Freiherr von Freyberg-Eisenberg-Allmendingen was a former 3. Garde-Regiment zu Fuß officer originally commissioned on the 27th of January 1906. He was born in Allmendingen on the 3rd of October 1884 and died there a hundred years later on the 11th of February 1984!

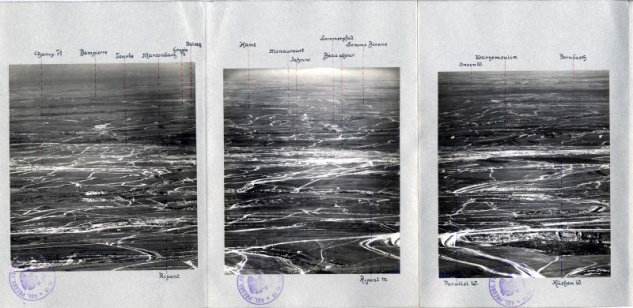

He served with 3. G.R.z.F. for most of his early career before receiving flight training with Flieger-Abteilung 1 from 1st May 1912 onwards. He remained in the Reichsheer after the war retiring in 1930 as a Major. Reactivated on 1 Oct 1932 as an Oberstleutnant, he eventually rose to the rank of Generalmajor on 1st June 1938 before finally retiring on the 31st of October 1943. He spent his war service as the District Airfield Commandant at Kolberg.

Von Freyberg was a holder of the Royal Houseorder of Hohenzollern with Swords. Bavarian Military Merit Order 1.10.15

Württemberg Friedrich Order-Knight 1st Class 23.11.17

Mecklenburg-Schwerin Friedrich Franz Cross 2nd Class.

Iron Cross 1st and 2nd Class

He held a Prussian Crown Order 4th Class from before the war, and was a Knight of the Maltese Order.

He already had a flying licence in 1913 and was the flying instructor of Prinz Friedrich-Karl. In the short clip below he gives us his opinion on von Falkenhayn, whom he was personally accquainted with. One of the last “Eagles of the Prussian Army”